The Russian rocket scientist who defected and taught at City.

Cold war spies, secret service agents and rocket science are usually reserved for Hollywood blockbusters. However, in 1967 they were very much reality for City’s Head of Aeronautical Engineering, Professor Grigori Tokaty.

After defecting from the Stalinist regime in 1948, Professor Grigori Tokaty sought refuge in Britain where he received a new identity and was appointed as Head of the Department of Aeronautics and Space Technology at the Northampton College of Advanced Technology, which later became City, University of London.

Working on both sides of the Space Race, Tokaty’s experience in aeronautical engineering saw him live a life not too dissimilar from the stories which populate our cinemas and television screens.

Early life and Soviet career

Born to a family of farmers in Ossetia, Russia in October 1909, Grigori Aleksandrovich Tokaev as he was known back then, lived through the end of the last Russian Tsar, Nicholas II.

Restricted by his humble origins, it was not until the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 that he was able to access education.

Tokaev joined the Communist Youth Movement and in 1927 entered higher education by enrolling a college for workers and peasants, called the Rabfak. His mathematical talents attracted the attention of his teachers and Tokaev progressed through higher education eventually enrolling in the Zhukovsky Air Force Engineering Academy, where he studied for six years before becoming head of the academy’s laboratory.

The outbreak of the Second World War halted his work at the academy and upon the siege of Leningrad in 1941 (St Petersburg today), he was sent to Moscow.

At the end of the war, Tokaev was a highly regarded member of the Communist Party and the USSR’s chief rocket scientist.

Tokaev was sent to USSR-occupied East Berlin and he advised the Kremlin on aeronautical weaponry including a rocket powered bomber that had the capacity to attack the United States.

The Cold War between the USSR and the West started to intensify and the Soviet Union began to suspect and arrest its own citizens, especially those who had spent time in foreign countries.

Tokaev was recalled home, however before he responded, he accidentally found out that military counter-intelligence SMERSH was about to arrest him, his wife and their young daughter. Fearful for his life, Tokaev crossed the border to British-occupied West Berlin and defected.

Life in Britain and at City

Upon resettling in Britain, Tokaev was given a new identity, the Ossetian version of his surname, Tokaty. Fears of assassination plagued his early years in Britain as he was the only soviet official to defect to the UK between 1945 and 1963.

Despite bringing much of his work in Russian space programmes, it was not until 1953 that he began lecturing at London universities, which he continued up until 1967, when he was appointed as Head of the Department of Aeronautics and Space Technology at the Northampton College of Advanced Technology, which later became City, University of London.

During a successful career at City, Tokaty was also invited to the United States to assist with its lunar programmes.

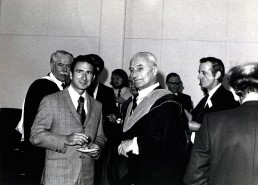

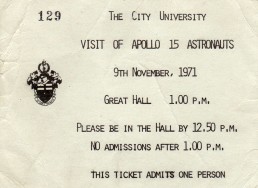

This experience made him instrumental in securing the visit of Apollo 15 astronauts James Irwin, David Scott and Alfred Worden to City in 1971.

Two months prior to their visit, the three astronauts had been part of Apollo 15, NASA’s fourth successful mission to the lunar surface. The crew had brought back the largest and most varied samples of lunar rock which were distributed to 201 investigators.

To mark the occasion, City’s Vice-Chancellor, Professor Sir James Tait was presented with a piece of heat shield from Apollo 15, after he had presented each astronaut with commemorative diplomas.

Speaking about the visit of Apollo 15, Sadi Ridah a former student of Tokaty’s class of 1972, who became a Professor in Fluid Mechanics and Thermodynamics at The University of Applied Science in Western Switzerland, Geneva, said:

“As aeronautical students we received a personal invitation to the visit, however so many of us could not get in as the Great Hall was packed with around 1,000 people within a minute of the announcement.

“Two things stand out in my mind about Professor Tokaty. We never had lectures with him, but he would often tell us about Soviet missile programmes in seminars. He was also a lover of chess and would play with the aeronautical engineering class.”

Later career and influence

Working with NASA during the sixties meant that Professor Tokaty’s career included developing aeronautical technology for both the USSR and the United States.

With this knowledge, Tokaty began lending his expertise to the media, where he commented in World at Wardocumentaries and would feature regularly in publications including The New Scientist. In one article in 1975, Tokaty detailed the USSR’s planned development of Salyut 1 – the first orbiting space station.

With a career in rocket science and knowledge of USSR secret services it is not difficult to find parallels between Tokaty’s life and the films, novels and television shows which surround us.

Author and historian Ben Macintyre wrote that Tokaty’s knowledge may have been an inspiration for certain villains in Ian Fleming’s James Bond series.

The Cold War period saw many propagated claims from both the West and the USSR, however as Tokaty detailed upon his defection to Britain, a Soviet secret service reporting directly to Stalin was a reality.

The counter intelligence operation known as SMERSH was formed in 1942 with the sole aim of scrutinising Nazi movement in Europe – however by the end of the Second World War this service turned its eyes to the West.

SMERSH played starring roles in Fleming’s spy novel series, for example where agents were sent to assassinate protagonist Bond in Casino Royale. However SMERSH’s main inclusion came inFrom Russia with Love, where the entire first section of the book is written from its point of view, planning for Bond’s elimination.

Auric Goldfinger, one of Fleming’s most notable antagonists is also revealed as a SMERSH treasurer.

SMERSH takes a different form in the cinematic adaptations, where it is renamed as SPECTRE, the very name that titled the 2015 film.

Tokaty also influenced American author Upton Sinclair where he included a fictional version of the academic in his historical fiction series, Lanny Budd.

In the final book of Sinclair’s work, the American protagonist Budd is saved from a Russian-owned prison in East Berlin by Tokaev himself. Both characters trade information with Tokaev detailing Stalin’s plans for attacking the United States and Budd assisting in his defection to Britain.

Legacy

Professor Grigori Tokaty retired from City in 1975 but acted as a visiting professor to institutions across the globe. He passed away aged 94 in Surrey in 2003.

His focus in space programme research balanced a technical yet philosophical mind questioning mankind’s placement in the universe.

In City’s 125 year history there are few with lives like Grigori Tokaty. Living and working through some of the world’s darkest and most important events made Tokaty a unique individual, who at a first glance would appear like any other academic engineer. However a closer look would reveal an extraordinary man light years away from the ordinary.