Dr Robert Mullineux Walmsley was the first ever Principal of the Northampton Institute, which thrives today as City, University of London. Chris Lines tells the story of a brilliant man whose vision is still keenly felt throughout higher education in the UK.

The rain is beating down on 8½ Dowgate Hill, the Hall of the Worshipful Company of Skinners. The year is 1896 and a large man cuts a bustling figure as he strides purposefully through the City of London and into the building.

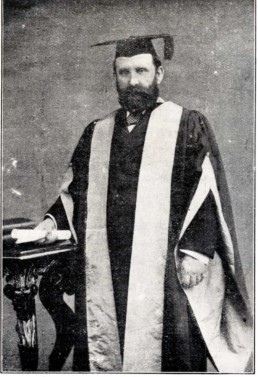

Mullineux Walmsley, although not tall, is broad and portly. He is, as ever, distinctively dressed in a grey frock-coat, putty-coloured spats and a distinguished top hat.

He has recently been appointed as the first Principal of the Northampton Institute and there is a great deal of work to be done. His task is made harder by the fact that the budding Institute’s impressive new building on St John Street is not yet finished. This temporary office, a mile and a half to the south at Skinners’ Hall, will have to suffice. But despite such adversity – and in a selfless manner typical of the man – Dr Walmsley is still happy to grant a journalist a few minutes for a brief interview.

The reporter asks him whether instructors at the Institute are experts in their respective fields. “Oh yes,” replies Walmsley, “for the constant aim of the instruction is to bring the students into actual touch with the subjects dealt with. The object is not to prepare the student to pass examination tests but to fit them to become a competent worker and thinker in the career that they have chosen.”

And it was ever thus. The Institute that we know today as City, University of London continues to have “academic excellence for business and the professions” as its mantra, having been set on this path by the formidable Walmsley, arguably the most remarkable individual in City’s long and proud history.

Following the Institute’s 1894 formation, Walmsley was appointed in September 1895 at the age of 41. Former City librarian S John Teague, in his 1980 book The City University: A History, noted that there were 94 applicants for the role and that Walmsley was considered to be “of outstanding ability”. It would be another two years until the Institute’s elegant home would officially open its doors but Walmsley was industrious from the outset.

Born the eldest of nine children in 1854, the premature death of Walmsley’s father left him with eight younger siblings to bring up, which perhaps goes some way to explain the level of self-sacrifice evident throughout his career. He undertook his early education in his birth city of Liverpool, before moving to London to complete a BSc degree in 1882. He remained in the capital and went on to become a Doctor of Science in 1886.

He started his career as a technical teacher at both Finsbury Technical College and the City & Guilds Institute, South Kensington. After a brief spell as Principal of Sindh Arts College (affiliated to the University of Bombay, India but based in Karachi, which is today the capital of Pakistan), he joined Heriot-Watt College, Edinburgh, where he became the first Professor of Electrical Engineering and Applied Physics prior to his appointment at the Northampton Institute. His publications include The Electric Current (1894) and Electricity in the Service of Man (1904).

Having formed with a remit to take on students aged 16-25, Walmsley gradually steered the Institute away from secondary teaching, fostering the university-level work. He oversaw the foundation of an Engineering Day College, set up links with industry that survive to this day and, perhaps most importantly of all, pioneered the notion of ‘sandwich’ courses; one of his greatest innovations and a project to which he devoted much time.

In 1903, Walmsley visited technical educational institutes in the United States. Impressed by what he saw, he proposed to his employer’s Governing Body that mechanical and electrical engineering courses be extended to four years’ duration, with students spending 5-6 months of their second and third years on placement at commercial workshops.

The governors agreed to try the system experimentally, provided Walmsley could demonstrate that manufacturers would be willing to take students on placement free of charge. He did so with great success, not only obtaining free placements but, in some cases, with small wages being paid to the students.

Each year, Walmsley personally visited the students during their placements across the UK and also abroad. One student went to Austria in 1905/06, with another heading to Genoa, Italy to work for Italian State Railways during 1908/09. Both were found passage to their respective host countries in the engine rooms of passenger ships.

Placement numbers continued to swell and by 1910/11 the Principal reported that he was unable to find students for all the places being offered by industry. And thus Walmsley’s innovative and successful scheme, inspired by US ‘cooperative colleges’, became the model for sandwich degrees in the UK. It was even mentioned in the 1911 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica.

Walmsley would carry out his visits during his holidays for nothing more than out-of-pocket expenses. And when an industry-wide lockout of engineers in 1922 threatened to make it almost impossible to find domestic placements for students, Teague notes that Walmsley “sent the Head of the Mechanical Engineering Department to Belgium and Switzerland and industrial experience was thus arranged for 13 students”.

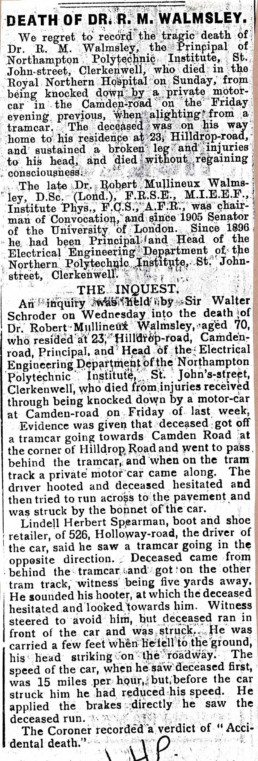

Walmsley died at the age of 70 after a tragic road traffic accident close to his home in Islington. News of his passing came as a devastating blow to governors, staff and students at the Institute where he was so fondly revered. One obituary noted that “the aim of the Governing Body is to keep [the Institute] a living memorial to the ability and devotion of its first Principal”. A bronze medallion portrait was later set on Hopton Wood stone and erected on the main staircase landing, while a Walmsley Memorial Fund was established to provide scholarships. More recently, his great-grandchildren, Andrew and Kate, visited City in 2016 and donated his academic gowns.

Walmsley was a true pioneer of higher education in the UK for many reasons and remained hugely influential and popular right up until his untimely death. The programme for a memorial organ recital held at the Institute the day after his passing was notable partly for its inclusion of Mendelssohn’s ‘He That Shall Endure to the End’. He had given everything to the Institute; it was his lifework and he would never be forgotten. But his greatest legacy is surely the sandwich course system that survives at City and many other universities nationwide today, across a broad range of disciplines.

Walmsley’s funeral was held on 19th June 1924. The Institute closed for the day as staff and students grieved. Shortly after his passing, the Institution of Electrical Engineers published their own heartfelt obituary. They noted that, following his appointment as the Northampton Institute’s first Principal, “with characteristic energy and enthusiasm [Walmsley] began the immense task of building up from small beginnings one of London’s greatest technical institutes”.

“Students and others who hold him in affectionate remembrance must feel, as they stand within the walls of the ‘Northampton’, the applicability of [Sir Christopher] Wren’s epitaph in St Paul’s Cathedral: ‘si monumentum requiris circumspice’.” If you seek his monument, look around you.

Contributor:

Chris Lines is an experienced journalist and editor who, since 2014, has worked as Publications Officer for City, University of London. He is also an alumnus of City’s School of Arts & Social Sciences (Periodical Journalism, 2003).